동북아역사재단 2018년 09월호 뉴스레터

- Shin An-sik (Visiting Professor, Konkuk University Department of His

Around 1,100 years ago, the kingdoms Goryeo (918-1392) and Later Baekje (892-936) were fiercely competing for hegemony on the Korean peninsula, while up north, the Khitans who founded the Liao dynasty newly rose to power as the Tang dynasty‘s fall brought chaos upon the Chinese mainland. And when the unified Song dynasty (960-1279) emerged in China, circumstances for intense international conflict were formed between Goryeo, the Song dynasty, and the Khitans.

Assuming Koguryo’s Heritage

After Unified Silla became disintegrated, Gyeon Hwon founded Later Baekje in what is now Jeolla Province in order to avenge Baekje, while Gung Ye founded Later Koguryo (901-918) at Songak to exact retribution upon Silla for destroying Koguryo. Gung Ye was later ousted by Wang Geon, who changed the kingdom's name to Goryeo and became its first king. The new name's resemblance to Koguryo hinted that Goryeo had recognized itself as the successor of Koguryo, which gave it reason to use Pyongyang as a base for pioneering northern territories. What Goryeo ultimately sought under the rule of its founder Wang Geon can be gleaned from what a merchant named Wang Chang-geun once said. "What our founder Wang Geon meant by first catching the chicken and then going after the duck is that after founding Goryeo, he would first acquire Gyerim (Silla) and then recover the lands of Koguryo around the Amnok River." This shows that Goryeo intended to not only inherit the histories of Unified Silla and Koguryo, but their former territories as well. Specifically mentioning the Amnok River, a symbol of northern lands, served as a major point of reference for Goryeo in defining its approach toward inheriting Koguryo and establishing its northward policy.

Goryeo's dual capital system also signifies the motivation for founding the kingdom and its intention to succeed Koguryo. As Goryeo relocated its capital from Cheolwon to Songak in 919, the second year of Wang Geon's reign, the new capital named "Gaegyeong" emerged as the center of Goryeo. Prior to the relocation in September 918, Koguryo's capital Pyongyang was designated as a major administrative district called "Dae dohobu," only to be renamed "Seogyeong" shortly afterwards. So, the capital's relocation to Gaegyeong occurred in January of the second year of Wang Geon's reign, and just a couple of months later in March, Pyongyang was given the new name Seogyeong, which meant "the western capital" based on the Chinese characters "seo" (西) for "west" and "gyeong" (京’) for "capital." So, the capital’s relocation to Gaegyeong and the renaming of Pyongyang to Seogyeong were carried out almost simultaneously to form a dual capital system for Goryeo.

Gaegyeong was recognized as the power base of Wang Geon's royal family as well as the bedrock of Goryeo, while Seogyeong was understood as the old capital or the vein of Goryeo's bedrock. Gaegyeong and Seogyeong could be regarded as a primary and secondary capital, but the two cities may have actually been of a similar stature during early Goryeo. Both Wang Geon and Goryeo's third king Jeongjong each devised plans to make Seogyeong the primary capital during their respective reigns. And while negotiating with the Khitan general Xiao Xunning during the reign of Goryeo's sixth king Seongjong, the Goryeo diplomat Seo Hui declared that Pyongyang was the capital of Goryeo as he said, "Our kingdom had been founded upon land that formerly belonged to Koguryo, which is why our kingdom is called Goryeo and our capital is Pyongyang." These instances suggest that early on in Goryeo, Gaegyeong and Seogyeong enjoyed an equal stature that went beyond the ordinary relationship between primary and secondary capitals. This is also how Seogyeong came to have a well-arranged fortress infrastructure that consisted of the royal palace where the king resides (jaeseong), the inner wall (referred to as naeseong or naseong), and the outer wall (referred to as either oeseong, wangseong, or hwangseong), allowing Seogyeong to evolve into a city comparable to Gaegyeong.

As an axis of the dual capital system, Seogyeong symbolized Goryeo's assumption of Koguryo's heritage, which determined Goryeo's dynastic identity and exercised a huge impact on Goryeo's awareness toward northern territories. This at the same time is what led Goryeo to experience territorial conflicts with its neighbors. In that respect, building fortress walls therefore reflected how Goryeo's northward policy was carried out. The walls had primarily been built to defend Goryeo's territory, but they were also aimed at setting up territorial boundaries with northern ethnicities.

Overcoming the Khitans' Invasion

Overcoming the Khitans' Invasion

Rather than being centered upon the idea of drawing exact national boundaries, Goryeo's earlier awareness toward northern territories was affected by how it recognized the former territories of Unified Silla and Koguryo. The Amnok River was pivotal in demarcating Goryeo's northernmost border, which made the river a crucial reference point for Goryeo in assuming Koguryo's heritage and establishing its northward policy. In general, inheriting history is associated with a dynasty's legitimacy and tends to inspire ideas about inheriting territory.

After founding Goryeo, Wang Geon solidified the kingdom's territorial foundation through Silla's submission and by destroying Later Baekje, but the circumstances up north remained unstable. On the surface, it was because of the rise of the Khitans, who brought down the Korean kingdom Balhae, as well as the northern-based Jurchens. Goryeo extended war with Later Baekje made it even more difficult to actively pioneer the northern regions. By designating Pyongyang as the western capital Seogyeong, Goryeo must have at least tried to express its willingness to actively pursue northern lands.

This is perhaps why the significance of Seogyeong was mentioned among the ten injunctions Wang Geon left to his future successors. The western capital was also used as a means to stabilize the Goryeo monarchs' authority after the end of Wang Geon's reign, particularly as a support base to defend such monarchic authority should it come under threat. Yet, Seogyeong was vulnerable in terms of defense for being located close to the northern regions, making it necessary to advance further up north beyond the Cheongcheon River and to later construct fortress walls in northern regions.

While designating Pyongyang as the western capital had to do with Goryeo's dynastic identity as the successor of Koguryo’s heritage, it also with stabilizing the northern lands so as to overcome threats from Later Baekje. The fact that patrols of Goryeo's northern regions were frequently performed during Wang Geon's reign suggests that Seogyeong is likely to have been used as a base for strengthening solidarity in those northern regions. Yet, early Goryeo's awareness of northern territories did tend to be limited by the rising Khitans and the less powerful Jurchens situated up north. Still, the Amnok River continued to remain at the center of Goryeo's awareness of northern lands and it took a war with the Khitans for Goryeo to secure the river basin as its territory.

What caused the Khitans to launch their first invasion of Goryeo in 993, the twelfth year of King Seongjong's reign, was not an acute diplomatic strife. Although the Khitans' forces did attack Goryeo first, they failed to aggressively advance further into Goryeo’s inlands or achieve notable success in combat. This can mainly be attributed to Goryeo's active defense, but at least for the Khitans, the cause for going to war and the benefits to be reaped from doing so had not been made obvious enough at the time.

The greatest achievement Goryeo made through the Khitans' first invasion was that it regained the northwestern region along the Amnok River through a peace conference between the Goryeo diplomat Seo Hui and the Khitan general Xiao Xunning in October of the twelfth year of King Seongjong's reign. The incident served as an opportunity to broaden Goryeo's awareness of northern territories and to externally secure a regional base for establishing Goryeo’s national border. Moreover, a territorial distinction between interior and exterior surrounding the Amnok River affected the way Goryeo formed its view of the world.

During its early days, Goryeo not only focused on establishing its identity as a unified kingdom, but also actively responded to the movements of northern ethnicities. Balhae's fall to the Khitans in 926, the ninth year of Wang Geon's reign, proved to be a turning point in Goryeo's northward policy that led to tense relations with the Khitans. While the people of Goryeo regarded those of the five dynasties and ten kingdoms as well as the Song dynasty in central China as civilized, it did not have the same regard for northern ethnicities such as the Khitans or Jurchens. Goryeo's policy to actively advance north therefore led to conflicts in Goryeo's relations with the Jurchens as well. Naturally, Goryeo's attitude toward the Khitans was as unfriendly as that toward the Jurchens. Goryeo's northward policy thereby limited Goryeo's early understanding of the northern ethnicities. Although that northward policy was what encouraged Balhae people and the Jurchens to migrate to Goryeo during its early years, it also turned into a source of frequent diplomatic friction between Goryeo and the Khitans. As a result, the Khitans launched their second attack on Goryeo in November 1010, the first year of King Hyeonjong's reign, and their third attack in December 1018, the ninth year of King Hyeonjong's reign.

The second and third attacks were primarily aimed at retrieving the northwestern region around the Amnok River that the Khitans had handed to Goryeo after their first attack and at forcing Goryeo to sever its diplomatic relations with the Song dynasty. However, the underlying intention for launching such attacks had been to intimidate Goryeo's territorial view of the world and affect the future of northern ethnicities like the Jurchens. As for Goryeo, refusing to return the northwestern region where it installed six garrison settlements since regaining the region and prevailing against the Khitans' second and third attacks instead offered a chance for Goryeo to broaden its world view.

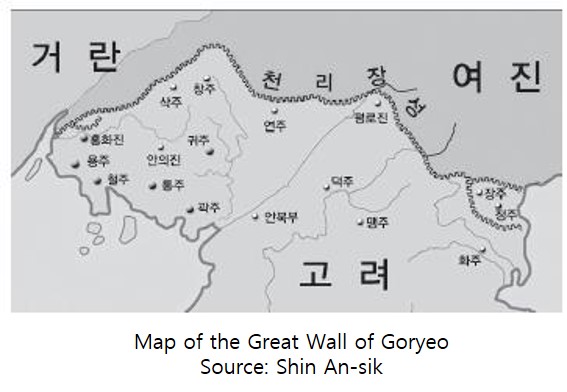

Goryeo jangseong, the Great Wall of Goryeo

Early Goryeo's gaze toward northern territories was fixed upon the northwestern region around the Amnok River. A turning point for that gaze emerged with the construction of Goryeo jangseong (高麗長城), or the Great Wall of Goryeo, from 1033, the second year of King Deokjong's reign. What's interesting is that even after installing the wall, Goryeo and the Khitans continued to engage in fierce territorial disputes over the region around the Amnok River.

What does Goryeo's understanding of the Amnok River as a point pivotal to its northern territorial pursuits, despite clashing with the Khitans over it, suggest? The river was situated close to Koguryo's former capital Gunganeseong (國內城), making the area relevant to the matter of establishing Goryeo's dynastic identity and providing Goryeo with a purpose for securing the area. This gave reason for the Khitans to question the Goryeo's motive behind its northern territorial pursuits, especially after going through diplomatic negotiations with the Goryeo diplomat Seo Hui through their first attack. So, it is likely that the Khitans intentionally clashed with Goryeo over the Amnok River to prevent Goryeo from growing dominant in the area. Regardless, its experience in the northwestern region provided Goryeo with a new purpose for its territorial awareness and pursuit of the northeastern region. The Great Wall of Goryeo was therefore not only a symbol of early Goryeo's awareness of northern territories but can be considered as progress made through Goryeo's northward policy.

The wall was also a result of overcoming the Khitans' persistent provocations surrounding the Amnok River so as to stop Goryeo from broadening its world view. After being attacked by the Khitans three times, Goryeo was able to methodically build a fortification system in the northwestern region that stretched out between the Daedong River, Cheongcheon River, and Amnok River. In the northeastern region, on the other hand, Goryeo failed to establish a firm line of defense based on mountains and rivers. On the surface, the great wall's construction seems to have provided Goryeo with an external demarcation between the Khitans and Jurchens, but it later developed into a cause that sparked conflicts with the Khitans in the northwestern region and with the Jurchens in the northeastern region.

The reason the Khitans sought to advance south of the Amnok River was to politically constrict Goryeo's world view and keep Goryeo's relations with the Song dynasty in check. For Goryeo, stabilizing the northwestern region was a matter of maintaining a geographical base since the region was important to its northward policy that revolved around its western capital Seogyeong. And by 1117, the twelfth year of King Yejong's reign, the Amnok River area came entirely under Goryeo's control as fortifications started to be installed along the river. Yet, it took the process of overcoming conflicts with northern ethnicities for Goryeo to develop enough of an awareness of northern territories to install fortifications. And circumstances entered a new phase as the armed forces of a Jurchen tribe called Wanyanbu (完顔部) took over the indirectly administered Chinese prefectures called jimizhou (羈縻州), signaling the formation of a new pluralistic East Asian order between Goryeo, the Song dynasty, the Khitans, and the Jurchens.

The rise of the Jurchens and their frequent border conflicts with Goryeo prompted Goryeo to launch a conquest of the Jurchens. The conquest took place between the reigns of King Sukjong and King Yejong, at a time when the Song dynasty was being intimidated by the Khitans and Goryeo’s frontier had become stabilized from engaging in exchange with the Khitans and from building the Great Wall of Goryeo. Goryeo was subsequently able to install nine fortresses in the region it conquered, thereby extending its territorial awareness of the northeastern region that had previously reached up to the garrison Gongheomjin (公嶮鎭) along the mountain ridge Seonchunryeong (先春嶺). Although Goryeo later returned the region with the nine fortresses to the Jurchens, Goryeo was still able to solidify its awareness of northern territories by seizing the Amnok River area when the Khitans weakened during the twelfth year of King Yejong’s reign. The significance of constructing the Great Wall of Goryeo thus lied in serving as a turning point for Goryeo’s awareness of northern territories.

If the great wall had been a fortification to protect Goryeo’s territory, how did Goryeo’s understanding of northern ethnicities beyond the wall change over time? After building the wall, Goryeo continued to accept incoming northern ethnicities throughout the reigns of King Deokjong, King Jeongjong, King Munjong, King Seonjong, King Sukjong, and King Yejong. Goryeo particularly allowed the Jurchens outside the wall to surrender and bestowed them with appointments and titles or indirectly controlled them by installing a jimizhou where the Jurchens were based. Goryeo’s incorporation of Jurchen lands was most prominent in 1073, the twenty-seventh year of King Munjong’s reign. That year, several east Jurchen villages asked to be incorporated into Goryeo’s territory and several west Jurchen tribes also sought to become a part of Goryeo. The number of incoming northern ethnicities became too high to limit their influx by installing fortifications.

Within a pluralistic international order, northern ethnicities tried to turn to either Goryeo, the Song dynasty, or the Khitans depending on which side they figured they would be able to benefit more from. This trend led to the formation of the suzerain-vassal system. Northern ethnicities were therefore classified in various ways in Goryeo, making them an insider or outsider based on which order they became incorporated into. This is similar to how China came to differentiate the “zhonghua” (中華) Chinese from the barbarians referred to as "yidi" (夷狄).

For instance, “hwaoe” (化外) in Goryeo referred to the Jurchens who sided with the Khitans and were hence outside Goryeo’s world view, whereas “hwanae” (化內) referred to the Jurchens who belonged within Goryeo’s world view. Even the Jurchens came to recognize themselves as either an insider “hwanaein” or an outsider “hwaoein,” which entailed the territorial notion of a frontier, and also ethnically distinguished “hyangmin” (鄕人), people from the same hometown, from “byeonmin” (邊民), people living in the border area. This indicates that while the Jurchens never truly became Goryeo citizens, those within Goryeo’s world view had indeed become subjects under the rule of Goryeo. Hence, the formation of Goryeo's world view and the process of its extension is perhaps what led to the Great Wall of Goryeo's construction, and that boundary between insiders and outsiders was linked to Goryeo's stature within the pluralistic international order in East Asia.