NORTHEAST ASIAN HISTORY FOUNDATION 01/2018

-

Lee Won-woo (Research fellow, NAHF Institute of Japanese Studies)

The year 2018 marks the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration in Japan. Despite its multiple facets, the Meiji Restoration is generally regarded as an event that internally prevented Japan from being colonized by the West and externally enabled Japan to invade and colonize its neighboring countries. Such invasions and colonizations continue to be sources of ongoing diplomatic friction between Korea, China, and Japan today, which in turn attests to the aggressive, violent nature of those who led the Meiji Restoration.

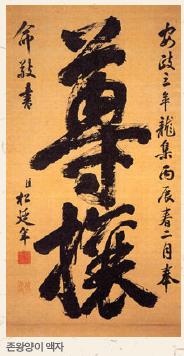

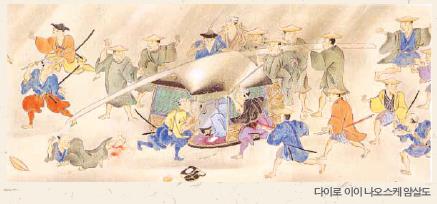

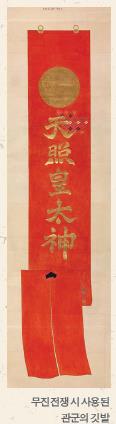

For those who study any subject from the transformational Bakumatsu period, it is easy to notice how frequently loyalists of the Sonno joi (尊王攘夷) movement committed terrorist acts like intimidation and assassination that were called Tenchu (天誅), or heaven's punishment for failing to revere the emperor and expel the barbarians. Such acts were carried out for the sake of expelling barbarians during the Bakumatsu period, for the sake of revising treaties during the first half of the Meiji Restoration, and for the sake of protecting the national polity in the 1930s and 1940s. The beginning was the Sakuradamon Incident in March 1860 when the Tairo, or Chief Minister, named Ii Naosuke (井伊直弼) was assassinated. The incident was followed by countless threats toward or assassination of nobility and commoners alike. Among the more well-known incidents are the assassination of Okubo Toshimichi (大久保利通) in May 1878, the assassination of Hara Takashi (原敬) in November 1921, the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi (犬養毅) during the May 15 Incident, and the assassination of Saito Makoto (斎藤実) and Takahashi Korekiyo (高橋是清) during the February 26 Incident of 1932. Yet, there are a couple of historical facts to keep in mind when examining the history of terrorism after the Meiji Restoration. One of them is that after going through the final days of the Muromachi bakufu as well as the Shokuho (Azuchi–Momoyama) period to gain control over the Japanese archipelago, the Edo bakufu had to foremost demonstrate its determination to end the Sengoku period by addressing sealed politics, or discussions about Japan as a state. Such discussions had previously been dominated by four to five key cabinet members of the government referred to as bakkaku (幕閣) who were usually vassals of the Tokugawa called fudai daimyo or members of the shogun’s council of elders called roju. In order to open politics up to other daimyos such as shinpan (親藩) or tozama daimyo, not to mention the emperor, court nobles (kuge), masterless samurai (ronin), and even wealthy farmers (gono) and merchants (gosho), lifting the ban on politics was more necessary than anything else.

Commodore Perry's visit to Japan in June 1853 followed by considerable pressure from the United States and other Western powers demanding that Japan open its ports and allow trade served as momentum for lifting the ban on politics in Japan. Coincidently, debates over the merits of opening Japan and engaging in foreign trade began to spread out and some Sonno joi loyalists even joined in them. In March 1854, the Edo bakufu finally gave in to pressure from the United States and signed a treaty of peace and amity (Kanagawa Treaty) with it. And by December 1857, the draft for a treaty of commerce was drawn that would open certain ports for free trade and allow diplomatic ministers to be stationed in Japan, signifying the country's opening.

Due to the need to form a consensus, at least among the ruling class, ahead of shifting its national policy from a closed to an open country, the Edo bakufu carried out two unprecedented measures. One was to share confidential records on talks with Townsend Harris, the United States Consul General to Japan, with all daimyos previously excluded from politics to collect feedback from them. The other was to gain the emperor's sanction on the treaty of commerce with the United States so as to preclude dissent from daimyos with disparate views as well as opposition from the three most noble branches of the Tokugawa clan. These measures signified that the bakufu lifted of its own accord the ban it had originally placed on politics in Japan.

Emperor Komei, who as a divine being of the system had until then endorsed the bakufu's rule of the state, practically rejected the bakufu's request for approval on a treaty of commerce with the United States. The emperor instead consulted with the heads of the five regent houses about the treaty, which became extended to 20 incumbent court nobles as well as the kurodonoto (蔵人頭), the equivalent of chief secretary to the emperor. This led to further political actions taken by 88 court nobles who presented themselves at the imperial palace as a form of protest, while hikurodo (非蔵人), trainees of the Chamberlain's office, as well as lower-class court officials joined the movement by submitting petitions asking for the treaty draft to be rejected. As the emperor broke away from the court's customs to expand the boundaries of political deliberation, politics irrevocably turned into a matter of public discussion. This became summed up by the slogan "kogi yoron" (公議輿論), meaning "government by public deliberation" that emerged during the transformational Bakumatsu period, ventured through complex layers of politics, and led to the Meiji Constitution's establishment.

The manifesto outlines their arguments that commercial relations against the country's interests had been established out of fear due to threats from the West, that the Tairo had to be killed as punishment for committing such a serious evil, and that they were dedicating themselves as instruments of heaven to place politics back on its rightful track. Apart from the fact that commoners became capable of discussing politics, it is easy to notice from statements in the manifesto that the wording was based on the samurai's code of conduct (bushido) of respecting the emperor's wishes and resisting against pressure from the enemy, regardless of whether such conducts result in victory or defeat. This means the bakufu's rationale of acknowledging the reality that Japan didn't stand a chance against the military might of Western powers and justifying the need to give in to their demands had been unacceptable to most samurais. No matter how crucial and urgent a matter may be, the Japanese customs and traditions of respecting the emperor should have been honored through the samurai spirit by immediately going to war to expel the barbarians. And the history of Japan thereafter proceeded precisely along that line of thought, in accordance with the rationales and sentiments of assassins who sought to defend traditions and the old system for heavenly purposes, and can therefore be referred to as the "original rightists" of Japan.

Fall of the Emperor's Authority

As the bakufu began to lose its political authority and capabilities after Ii Naosuke's assassination, terrorist incidents increasingly occurred not only at Edo, but at Kyoto as well, and against a wider range of targets that even included those closely serving the emperor. Threats and assassinations by masterless samurais who were sonno joi advocates particularly bred distrust among the emperor and court nobles, making circumstances chaotic and difficult to tell right from wrong. The royal court's policies became pointless under pressure and threats from masterless samurais, and the emperor was no longer able to take the initiative in making policy decisions. This in turn caused the emperor and the royal court to lose their political authority and capabilities. Up until the first half of 1858, Emperor Komei took the lead in expelling the barbarians by refusing to sanction a treaty with a foreign power and came to stand in the center of politics during the Bakumatsu period. And the emperor's authority rapidly increased as a symbol of expelling barbarians up until he ended up ratifying treaties with foreign countries in October 1865. What becomes questionable is whether the emperor was actually revered as his authority rapidly increased as a symbol of expelling barbarians during the Bakumatsu period. Because there was a disparity between the emperor's public image and the emperor as an individual human being. Emperor Komei's political force propelled by the idea of expelling barbarians began to lose momentum from the end of 1858 due to serious oppression from the bakufu and started to go astray under the influence of the bakufu, sonno joi advocates, and major domains. So, although his authority reached a peak from the end of 1862 up to the middle of 1863, Emperor Komei's authority as a human being grew weaker with the passing of each day.

For instance, in his letter dated April 22, 1863 to Nakagawano Miya (中川宮), Emperor Komei complains that "despite expressing my wishes to postpone the trip to campaign the expulsion of barbarians scheduled for the 10th of May due to a chronic case of dizziness, court nobles and statesmen like Sanjo Sanetomi are pushing me to go ahead with the trip, even if it means forcing me to travel on a palanquin." This obviously indicates that several court nobles and masterless samurais held sway over the royal court at the time.

A series of measures the royal court took under the pretext of upholding its authority had not been part of the emperor's idea, but the result of an agreement made between several court nobles and masterless samurais. Not only was the emperor not taken seriously, but this eventually led to the trend of actively interpreting the emperor's wishes, in other words "disobeying imperial edicts." Hence came the all too famous statement by Okubo Toshimichi who said "an unjust imperial order is not an imperial order" (非義勅命ハ勅命ニ有ラス候).

The tradition upheld today among Japanese politicians of declaring that the emperor should be revered, but actually distorting or ignoring the emperor's wishes may have originated from the times of the Meiji Restoration. So, when we hear Japanese right-wingers comment about "revering the emperor," we should be more aware of the history behind what the phrase implies.