동북아역사재단 2010년 02월호 뉴스레터

On October 29, 2009, the Tokyo High Court dismissed the second appeal by the victim, survivor, and victims' family groups of forced mobilization during Japanese colonial rule for the "Case of Military and Civilian Conscripts Residing in Korea." The lawsuit was filed against the Japanese government in June 2001. It demands the following: 1) Apology for the enshrinement of Koreans at Yasukuni Shrine and the return of their remains; 2) Compensation to those detained in Siberia; and 3) Compensation for unpaid wages. In May 2006, the Tokyo District Court dismissed the case on the grounds that the plaintiff's right to file a claim had expired pursuant to the "Agreement between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation." We met with Lee Hui-ja, head of the Council for the Compensation of the Victims of the Asia-Pacific War, about the lawsuit. For over 20 years, Lee has been carrying out a difficult fight against the Japanese government to remove her father's name from Yasukuni Shrine.

After you lost the last case, you said in an interview, "We started the fight not to win or lose a court case but to leave a record of the conscience of Japan's judiciary. What have been some changes or achievements over the past eight years?

There are now organizations that support us in Japan, including "No Joint Enshrinement [NO 合祀]" and the "Case Support Group for Japanese Military and Civilian Conscripts."The greatest achievement is that we now have more means to spread the opinions and wants of victims in Japan and Korea. During the course of the case, I realized that we desperately needed a special legislation for uncovering the truth, so I led efforts to enact the "Special Act to Find the Truth of Compulsory Mobilization Damage under the Colonial Rule of Japan" ("Special Act" hereafter). While I lost the case, the lawsuit was meaningful in that it served as an impetus for the Special Act. People say I lost because I lost the court case, but that's not how I look at it.

It is said to be the largest post-war compensation lawsuit. Eight years have passed. Please tell us about what has happened with the case.

The plaintiffs say that this lawsuit includes just about all there is to post-war compensation. It includes our demands to the Japanese government not just concerning compensation but on all fronts, including the Yasukuni joint enshrinement, the repatriation of victims'remains, the disclosure of records for unconfirmed families of victims, and the return of financial deposits made by the victims. People without records cannot file a lawsuit. Therefore, we got the testimonial of every single plaintiff, 416 in all. We then located pre-liberation (1945) Japanese work/school registers that listed the Japanized names of Koreans. In many cases, the only thing the victims' children knew was that their fathers had not returned from Japan; they had no idea whether their fathers had been military conscripts, civilian conscripts, or laborers for private businesses. Therefore, we took down the demands of each surviving family member and submitted them to the Japanese side.

We imagine that your expectations have been high since the election of Prime Minister Hatoyama.

Even if the Hatoyama cabinet does tackle the compensation issue, I don't think there will be significant changes. I don't have any expectations. Nonetheless, the Japanese government has agreed to disclose to the Korean government this March the records of financial deposits made by between 60,000 and 260,000 conscripts. These records could be very helpful to those victims' families that had not been able to locate any records so far.

Will the records on financial deposits made by Korean conscripts help with the lawsuit?

'In addition to the Special Act, there is also the "Law to Provide Support to the Victims of Forced Overseas Mobilization around the Time of the Pacific War."If the deposit records show that there have been unpaid wages for a particular victim, his family can probably receive government support pursuant to the latter law. But we don't know yet what the government plans to do, so it is too early to say whether or not the records will be helpful.

As someone who felt the need for and led the enactment of the Special Act, is there anything you would like to ask of the Korean government?

If a government doesn't do what it's supposed to do, that in and of itself leaves a stain on history. In 1974, the Korean government enacted a law that provided 300,000 won per head in compensation to those who died before liberation due to Japan's forced mobilization. The law was in force for a short period of time, after which the government refused to provide any further compensations to the victims. However, the government did not actively promote the program, so many people did not even know about it. Furthermore, there were many victims who had sustained damage other than death. I think it was wrong of the government to have concluded the whole matter through a temporary, one-time legislation. I hope the current government does not leave this problem unresolved.

The lawsuit would have been difficult without the solidarity of the international community of victims' families. How do you cooperate with the victims' families in Korea, Taiwan, and Okinawa (Japan)?

It was in 2002 that I first met Goajin Sumei, an indigenous Taiwanese legislator who spearheads the Joint Action against Yasukuni. I met him again in 2003 and 2003. We decided to work together against the unauthorized joint enshrinement at Yasukuni. Our collaboration began in 2005. We also work with the victims' families in Okinawa. According to the argument provided by Yasukuni Shrine for the joint enshrinement, it may only be natural that Japanese citizens who died during the war are enshrined. In Okinawa, however, local residents were herded into a cave and were forced to commit suicide. It is very difficult to say these people put an end to their lives in the service of Japan. That is why there is a movement in Okinawa calling for an end to the joint enshrinement and that is why they have joined us in our lawsuit against Yasukuni Shrine.

What would you like to ask of the Northeast Asian History Foundation?

The issues with Japan are difficult to resolve because the 1965 Korea-Japan Basic Treaty cannot be reversed. However, academic errors can be rectified. One of the 7 key issues the Foundation deals with is the Yasukuni Shrine issue. I hope the Foundation undertakes studies on the illegitimacy of the Yasukuni Shrine and the lawsuit against the joint enshrinement. I wish for the findings to be promoted throughout the international community. We organized an exhibition on the Yasukuni Shrine last year. Many people agree on the illegitimacy of the Yasukuni Shrine but very few know the exact reasons why. The exhibition was very effective. We are planning an exhibition in Japan in 2010. Thanks to the Foundation's support, we have gotten the opportunity to raise international awareness on the Yasukuni Shrine issue.

What are your plans for 2010?

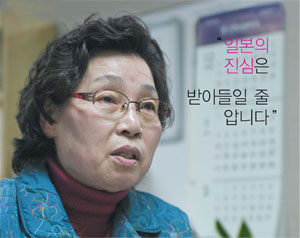

We are getting ready for our appeal at the Supreme Court of Japan. The case for the abrogation of joint enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine is still in progress. We haven't yet gotten the first ruling, and it looks like it will take some time. We plan to undertake activities that highlight the illegitimacy of Yasukuni Shrine and that call on the conscience of the Japanese judiciary, something the Japanese government have avoided doing. The lawsuits are not just about winning. The objective of our activities is to let the Japanese government and the international community hear and feel the anguish of those people who lost their parents under colonial rule and those people who cannot prove that their fathers have never returned from Japan because of the lack of documentary evidence. I want to appeal to the United Nations regarding the wrongful rulings of the Japanese courts. I also want to properly organize my activities so far. My activities are not just for the compensation. What I really want is a sincere apology from Japan. We cannot live as enemies of Japan. We need to know how to accept the sincerity of the Japanese government if and when it is extended to us. I hope the victims don't get caught up in compensation matters.

[Lee Hui-ja]

She is currently the co-representative of the Council for the Compensation of the Victims of the Asia-Pacific War and the co-representative of the Korea Committee for the Joint Action against Yasukuni. Lee began working with a Pacific War victims group in 1992 to find out whether her father was alive or not. Her father Lee Sa-hyeon was forcefully mobilized in February 1944 and passed away as a conscript. In 1997, Lee learned that her father was enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine. In June 2001, with 252 victims' family members as plaintiffs, Lee filed a lawsuit with the Tokyo District Court against the Japanese government demanding the abrogation of the joint enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine, the repatriation of the victims' remains, and compensation. In February 2007, Lee filed a lawsuit against Yasukuni Shrine seeking the abrogation of joint enshrinement.