NORTHEAST ASIAN HISTORY FOUNDATION 07/2013

-

Written by Jung In-seob, Professor of Seoul National University Law School

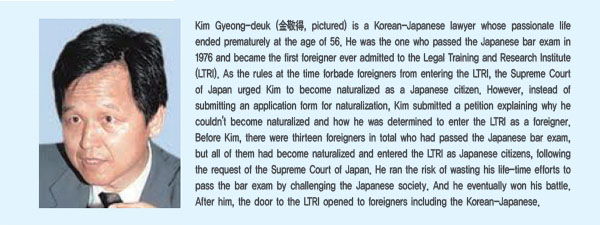

Entering the LTRI Without Becoming Naturalized as a Japanese Citizen

Kim Gyeong-deuk is a Korean-Japanese born in the city of Wakayama (和歌山) in Japan to Korean parents who moved to Japan during its imperial years. Until he turned twenty-three when he graduated from Waseda University, Kim was a typical Korean-Japanese who used a Japanese name and regarded his Korean descent as something to hide and be ashamed of. Obviously, he didn't speak any Korean, either. After graduation from university, he faced the harsh reality that it was hard for the Korean-Japanese to land a job they wanted. And while preparing to take the bar exam in order to challenge the discrimination prevalent in the Japanese society, he decided to use his original Korean name Kim Gyeong-deuk. Later, Kim often recalled the year when he turned twenty-three as the first year of his real life on his own terms.

Kim said he felt very painful and miserable to disguise himself as Japanese simply to avoid discrimination in Japan. He began to ask himself: What did I do wrong to deserve this? He decided that his pain was not his fault but the fault of the Japanese society that was discriminating people like him. He thought that passing the bar exam and entering the LTRI after becoming naturalized as a Japanese citizen, though it may solve his personal problems, was nothing more than escape from discrimination. He also thought that if he became naturalized as a Japanese citizen, it would haunt him forever and rob him of the meaning of his existence. Kim with a small physique, less than 160 centimeters in height, threw himself against the thick wall of discrimination standing tall in the Japanese society.

He submitted a total of six petitions and written opinions to the Supreme Court of Japan explaining why he couldn't become naturalized as a Japanese citizen. Finally, the Supreme Court of Japan added "except for those recognized by the Supreme Court of Japan" in parentheses to one of the reasons for disqualification for the Japanese bar exam: "those who are not Japanese citizens," and gave Kim Gyeong-deuk permission to enter the LTRI in March 1977. This was a sort of retroactive relief through ex post facto law.

Lawyer Kim Gyeong-deuk as an Advocate for Korean-Japanese Human Rights Movements

For about a quarter of a century after he completed the LTRI and was admitted to the bar, Kim Gyung-deuk had been in every scene of human rights movement for the Korean-Japanese. He opened "Woori Law Office" in 1985 as a practicing lawyer, and served in countless public positions as member of the Organization of Korean Residents in Japan (Mindan) Committee for the Protection of Rights and Interests, chairman of the Legal Status Subcommittee under the Korean-Japanese Research Committee under Mindan, advisor for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of South Korea on the matter of descendants of the Korean-Japanese, member of the Post-War Compensation Committee for the Korean Japanese under Mindan, member of Mindan's Central Committee, and director of Korean YMCA in Japan. He defended the Korean-Japanese in what have now become legendary lawsuits advocating their human rights, including Kim Hyun-jo's lawsuit claiming national pension, the lawsuit seeking the return of Koreans remaining in Sakhalin, Lee Sang-ho's lawsuit refusing to register his fingerprints, former civilian clerk for the military Seok Seong-gi's lawsuit claiming the payment of disability pension. Song Shin-do's lawsuit for the victims of military sexual slavery, and Jung Hyang-gyun's lawsuit seeking to confirm his qualification to take the exams to become a government official. He won sometimes, and other times he lost. If and when he lost a case, he prepared the next case to fight discrimination in the Japanese society. It was amazing, almost mysterious, how such a small man like him could be so full of fight and fervor.

Judge Izumi (泉德治), who, as Head of the Office of Appointment of the Supreme Court of Japan at the time, urged Kim to become naturalized as a Japanese citizen when he passed the bar exam, understood the reality of discrimination in Japan through his case, and served as a working-level mediator until the Supreme Court of Japan permitted his entrance to the LTRI. Later, Izumi became a judge at the Supreme Court of Japan and known for his particularly many separate opinions. The lawsuit filed by Chung Hyang-gyun claiming that he had been denied promotion just because he was Korean-Japanese lasted as long as 11 years. In this case, the plaintiff who won in the second trial finally lost in the final instance in the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court Judge Izumi who participated in this decision reportedly wrote in his journal on the date for Kim Gyeong-deuk's hearing: "Lawyer Kim delivered a fiery speech." In this decision given against the plaintiff, Judge Izumi presented an opposing opinion, arguing that permanent residents of Japan, like the Korean-Japanese, should be given opportunities for self-fulfillment..

Kim Gyeong-deuk Leading the Korean-Japanese Human Rights Protection Movement at its Peak

Kim was more than just a human rights lawyer. From the mid-1980s through the 1990s while he was most active, the Korean-Japanese human rights protection movement was at its peak in connection with the revival of the negotiation between Korea and Japan over the legal status of descendents of Koreans in Japan. And in this human rights movement, he was the best at connecting and coordinating the three parties, that is the Korean-Japanese community, Japanese intellectuals who supported them, and the South Korean government officials and those Koreans interested in this issue.

Once the legal status negotiation was almost completed, he decided that the Korean-Japanese should be given the right to vote if they were to truly gain their rights. He argued that the Korean-Japanese should exercise their rights to vote in local administration as foreign residents in Japan, and also exercise their rights to vote in government administration as people. He thought that this system would allow the Korean-Japanese living all their lives as foreigners in Japan to establish their identity. Today, South Korea recognizes the right for Koreans overseas to case an absentee ballot. However, the right of the Korean-Japanese to vote in local administration, which he dreamed of, has yet to be While he had the nerve and courage to challenge the Supreme Court of Japan, saying that he would rather give up his legal career than become naturalized as a Japanese citizen, he was always humble, kind, and devoted to his family. While he had the persistence and determination to never give up his goals, he had good social skills that won people over to his side. Kim Gyeong-deuk, he was one of Koreans overseas we are most proud of.

On the occasion of the first anniversary of his death, a memorial rally was held in Tokyo in February 2006 where about 600 people from across Japan and Korea gathered together, mourning his early parting. And the South Korean government awarded him a national medal of honor in recognition of his service. A book in memory of him (辯護士 金敬得 追悼集(新幹社)) was also published. Also in South Korea, on December 11, 2007, an event was held in memory of him and on the publication of Remembering Korean-Japanese Lawyer Kimg Gyeong-deuk (Kyungin Munwhasa), at the Press Center in Seoul, where many acquaintances of his attended and missed him. I feel lucky to have been personally acquainted with a man like Kim Gyung-deuk, and I miss him, wondering how many more giants like him I could meet in my life. Kim left this world in February 2005, but his son and daughter, as lawyers in Japan, are following in his footsteps.