NORTHEAST ASIAN HISTORY FOUNDATION 08/2010

-

Kim Jong-won Film historian, film critic

제2회 역사영상 심포지엄

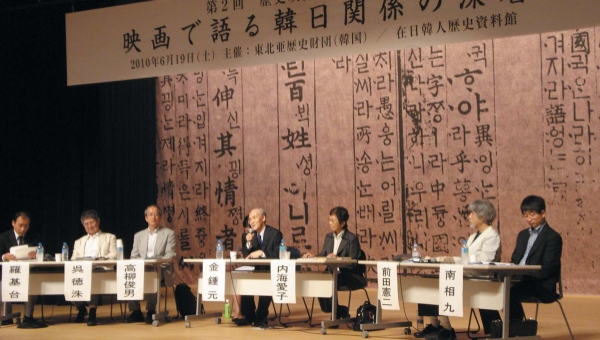

제2회 역사영상 심포지엄In the run-up to the centennial of Japan's forced annexation of Korea (August 29), the symposium "In-Depth Exploration of Korea-Japan Relations in Film" was held on the June 19. It took place at the Korean Cultural Center in Tokyo and was sponsored by the Northeast Asian History Foundation. The symposium tied history, which can often be stuffy and dull, with film. It was thus an unusual symposium which the general public found accessible.

Preceding the main event, there was a screening of Sarang-ui Maengsei [Vow of Love], Sarang-ui Muksirok [The Apocalypse of Love], and Hotaru [Firefly]. These films, relevant to the theme of the symposium, attracted an audience of some 300 and generated interest in the symposium itself. This was the second video symposium following last year's symposium "Joseon Films during the Pacific War" held in Beppu, Japan. Six Korean and Japanese historians and film experts participated as presenters and panelists this year.

I presented a paper entitled "Korea-Japan Relations through Film: Conflict and Reconciliation." The paper's premise is that Korean cinema has congenital defects given that Japanese capital and technology had given rise to it. It is thus argued that until the Korean Wave (refers to the popularity of Korean culture around the world, especially in Asia), Korean cinema went through great hardship. I categorized Geudae-wa Na [You and Me] (1941, Heo Yeong) and Sarang-ui Maengsei [Vow of Love] (1945, Choi In-gyu & Imai Tadashi) as representative examples of pro-Japanese, government-controlled films that reflect Japan's view of Korea as being subordinate to it. Director Choi In-gyu's Jayu Manse [Hurrah! For Freedom] (1946) is classified as the first anti-Japanese film, reflecting changing trends following Korea's liberation. Classified as films of reconciliation are Director Kim Su-yong's Sarang-ui Muksirok [The Apocalypse of Love] (1995)—about Tauchi Chizuko, a Japanese woman who devoted her life to taking care of Korean orphans—and Director Furuhata Yasuo's Hotaru [Firefly] (2001), a Japanese film. I concluded that universal human values of love and fraternity hold the key to realizing equal Korea-Japan relations and emphasized that it is important for perpetrators to adopt an attitude of remorse.

Interest in the encounter between history and film

Utsumi Aiko [內海愛子], visiting professor at the graduate school in Waseda University, presented a paper entitled "'Japanese-korean Unity' in Government-Commissioned Films." She calls our attention to the discovery of about a quarter of the film reel for Geudae-wa Na [You and Me] (Maeil Business Newspaper). Geudae-wa Na was a propaganda film for Japan's assimilation policy targeting Koreans. The paper discusses the status of this film and Director Hinatsu Eitaro's life, focusing on how Heo Yeong [許泳], a Korean, lived as a Japanese under the name Hinatsu Eitaro [日夏英太郞].

Professor Utsumi also talked about Gunyong Yeolcha [Military Train] (1938, Seo Gwang-jae), which was released before Geudae-wa Na [You and Me], as well as propaganda films promoting military conscription and the "oneness of Japan and Korea". These propaganda films were produced toward the end of Japan's colonial rule, after the Governor-General's film regulation policy went into effect. Examples cited include Jip-eopneun Cheonsa [Homeless Angel] (1941, Choi In-gyu), Bando-ui Bom [Spring on the Korean Peninsula] (1941, Lee Byeong-il), Jiwonbyeong [Volunteer Soldier] (1941, Ahn Seok-yeong), and Sarang-ui Maengseo [Vow of Love] (1945).

The discussion following the presentation of the paper proceeded without any issues of contention. Professor Takayanagi Toshio [高柳俊男] of Hosei University mentioned Director Kim Jae-beom's documentary on Heo-yeong, who had lived under different names in Joseon, Japan, and Indonesia. He reminisced about how impressed he was by the director of the Film Archive who said that even a shameful past is our legacy and went out in search of the film reel for Geudae-wa Na. Professor Takayanagi went on to stress that it is important for there to be a joint effort to create a film archive accessible to both Korean and Japanese experts.

Film director Maeda Kenji [前田憲二] discussed how Japanese culture is founded on Korea-Japan relations. To illustrate his point, Maeda examines two feature-length documentary films, including Dozokunoransei[土俗の乱声] (1991), which deals with ancient Joseon culture introduced to Japan. He also looks at Baekmanin-ui Sinsaetaryeong [The Painful Tales of Millions] (2000), which details the realities of forced Korean military and labor conscripts under Japanese colonial rule, as well as Mimizuka[Grave of Ears] (2009), which features Toyotomi Hideyoshi's acts of cruelty in South Korea, North Korea, and Japan.

Film director Oh Deok-su, a Korean expatriate in Japan, commented on Director Imai Tadashi's accomplishments. Imai, who was the co-director of Sarang-ui Maengseo, directed Aoi Sanmakyu [The Green Mountains] (1949) and became a leading anti-war, pro-human rights film director as well as a critic of Japanese society in the postwar era. His movies were selected five times as the number one film by Kinema Junpo, a Japanese film magazine. Director Oh lamented that it was a tragedy of the time that such a person had participated in the production of a war propaganda film. Citing Suicide Squad of Watchtower(1943)—another film set in colonial Joseon—as another example, Director Oh remarked that it is difficult to reconcile Imai's propaganda films with his later works.

From domination and conflict to a path for mutual advancement

Research Fellow Nam Sang-gu (Northeast Asian History Foundation) focused on Tak Gyeong-hyeon [卓庚鉉], a Korean member of the Kamikaze squad, to shed light on the dark history of Korea-Japan relations. Tak was a figure who had to assume two identities, one as the Korean Tak Gyeong-hyeon and the other as the Japanese Kamikaze squad member Mitsuyama Hirobumi [光山文傳]. He is taken as a symbol of Korea-Japan relations during the Japanese colonial period. Against the historical backdrop of Japan's policy forcing Koreans to adopt Japanese names, assimilation policy targeting Koreans, and military volunteer system, the demise of Tak is linked to Second Lieutenant Murai in Sarang-ui Maengseo and Lieutenant Kaneyama (Korean name: Kim Seon-jae) in Hotaru. In the meantime, the depiction of the relationship between Tauchi Chizuko, the Japanese heroine of Sarang-ui Muksirok, and her husband Yun Chi-ho is regarded as a representation of reconciliation.

As President Chung Jae-jeong succinctly summarized in his opening remarks, the key concept tying the three films on which this symposium focused is "war and humans." The present task for Korea and Japan is to seek wisdom enabling harmonious coexistence and mutual advancement irrespective of the ethnic differences and territorial borders separating us. For this to happen, Koreans must first wash away the painful memory of the Pacific War. To this end, Japan and Korea, as the perpetrator and the victim, respectively, must strive to learn from the lessons of the Japanese colonial period. It is in this regard that this year's video symposium held great significance.